It’s difficult to overstate the impact Virgin has had on airline travel. (Photo: APP: Mal Fairclough)

It’s difficult to overstate the impact Virgin has had on airline travel. (Photo: APP: Mal Fairclough)

Former Qantas boss Geoff Dixon, who took over running Qantas just months before the demise of Ansett Airlines, was under no illusions about the difficulties facing a second carrier.

“The problem with the Australian market is that it’s big enough for probably one-and-a-half airlines,” he quipped privately, years later.

Australian aviation is littered with the names of airline hopefuls that became casualties: Impulse, East West, Compass, Ozjet and, of course, Ansett. That’s just in the past 20 years.

Ansett went under in September 2001, just a week after two airliners were crashed into the World Trade Centre in New York, an event that halted almost all global air traffic and crippled the industry as America shut its borders.

But it had been on the skids for years and, shortly before its demise, the Air New Zealand-owned operator was losing around $1.3 million a day.

The Australian market is only big enough for one-and-a-half airlines, former Qantas boss Geoff Dixon once joked. (Photo: Dean Lewins, AAP)

The Australian market is only big enough for one-and-a-half airlines, former Qantas boss Geoff Dixon once joked. (Photo: Dean Lewins, AAP)

The parallels with Virgin’s long-expected descent into voluntary administration are uncanny — a shutdown of global air travel undermining the already precarious financial position of Australia’s second carrier.

But there are huge differences as well. Ansett’s demise was hastened by the emergence of Virgin Blue — the forerunner to Virgin Australia — and Impulse. Both new entrants were aggressively undercutting fares and, while tiny, were eating into the profits of both Qantas and Ansett.

In one of his first moves as Qantas boss, Geoff Dixon snapped up the loss-making Impulse, leaving Virgin to attack Ansett.

Unlike now, however, once the poorly managed Ansett went under, there was a competitor already on the tarmac ready to muscle up to Qantas and to absorb some of Ansett’s workforce.

That won’t be happening this time around. While the administrators from accounting firm Deloitte talk of reconstruction and refinancing, those avenues have been well traversed by an increasingly desperate Virgin Australia management over the past few months.

Each of the stricken airline’s major shareholders — Singapore Airlines, Etihad, Chinese carriers Nanshan and HNA, and Richard Branson — have abandoned pleas to come to its aid. All have more pressing problems at home.

A sale is likely to render their investments worthless, given it is hocked to the eyeballs with $5.3 billion of debt. As a large slice of that debt is unsecured, many of the lenders will be pressured into taking a serious haircut, while most will be lucky to retrieve any money at all.

Ansett Airways, founded by Reginald Ansett, spent 65 years flying the Australian skies. The company went under in 2001. (Supplied: Sir Reginal Ansett Transport Museum)

For weeks, the financial press has been salivating over the prospect of a private equity firm entering the fray as a “white knight”. It’s a view echoed by Federal Government ministers who are confident a private enterprise solution would be best for the company and the country.

Ultimately, they might be correct. But that’s neither the nature of private equity firms, nor the motivation.

They pick over the carcass of failed corporate vehicles, removing anything of value. Then they blacken the tyres, tart up the duco, throw some sawdust in the diff and hopefully flog it off for a huge profit to unsuspecting buyers.

Just ask anyone who bought shares in the Myer or Dick Smith floats.

To believe a private equity-led Virgin would be flying anything other than the country’s most profitable routes — Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane — requires a good deal of imagination.

So, who wins?

Never in his wildest dreams would Qantas boss Alan Joyce have imagined such an opportunity would simply land in his lap.

For years, Virgin was a constant torment. Its early incarnation as a low-cost carrier forced Dixon to take Virgin on at its own game. He set up Jetstar and appointed Joyce to run the new no-frills service.

When Dixon departed in 2008, as the global financial crisis was in full swing, Joyce took his place, nudging out another senior Qantas executive John Borghetti in the process.

Borghetti quickly shifted from colleague to competitor when he took up the reins at Virgin with a radical change in strategy.

Rather than low-cost carrier — a strategy that had failed to deliver profits for Virgin shareholders — Borghetti attacked Qantas on its traditional turf, as a full-service airline. The el-cheapo holiday and tourist service instead chased business clients.

The ensuing stoush between Joyce and Borghetti brought Qantas to its knees. The bruising battle for market share pushed Qantas deeply into the red with a $2.8 billion loss in 2014. So dire was the situation, Joyce was forced to go cap in hand to the Federal Government begging for a guarantee on its debt.

Then treasurer Joe Hockey was tempted but was howled down. Now, with the situation reversed, a defiant Joyce has been adamant that any federal bailout be industry wide, rather than for a single company.

If Virgin survives voluntary administration, it will be in a far more modest form. (Photo: ABC News: Andrew O’Connor)

If Virgin survives voluntary administration, it will be in a far more modest form. (Photo: ABC News: Andrew O’Connor)

And who loses?

That’d be you and me. That is, apart from the shareholders and the debt owners and quite possibly a large portion of Virgin’s 10,000 direct employees.

A dominant Qantas will not be under the same pressure to offer discount fares. Neither will Jetstar, despite its status as a low-cost carrier. If it does expand its services, some Virgin employees may cross the terminal floor.

It’s difficult to overstate the impact Virgin has had on airline travel. From day one, it forced fares down.

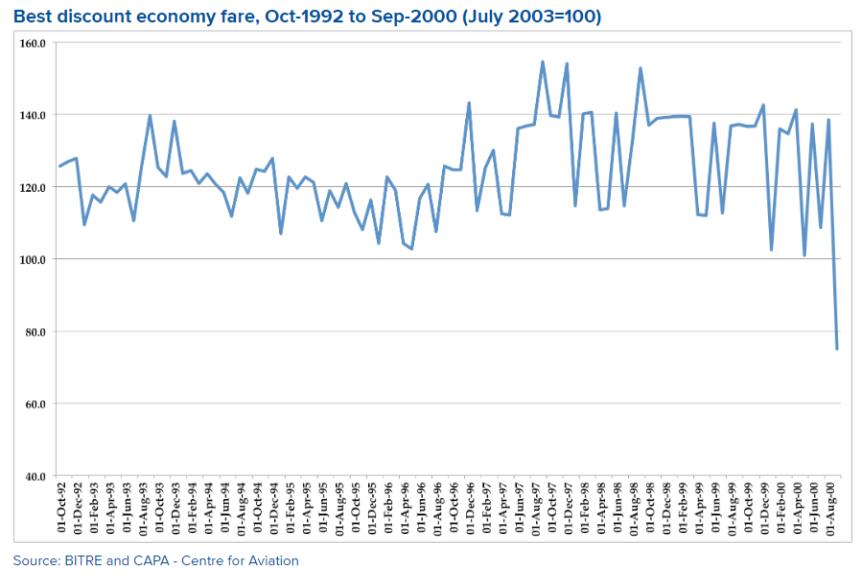

In August 2000, its first full month of operation and a year before Ansett’s demise, discount economy airfares slid more than 40 per cent below the lowest fare in the previous two years as this graph shows.

Airfares dropped sharply when Virgin Blue first entered the market to take on Qantas and Ansett. (Supplied: BITRE and CAPA – Centre for Aviation)

Airfares dropped sharply when Virgin Blue first entered the market to take on Qantas and Ansett. (Supplied: BITRE and CAPA – Centre for Aviation)

Borghetti also attacked Qantas on its international routes, not by launching Virgin Australia-owned services but through strategic alliances with other big carriers.

It picked off Etihad before Qantas could make a move and stitched up a deal with Singapore Airlines that delivered it access across Asia, Africa and Europe. A deal with US carrier Delta made its global network complete.

While the transformation was a success, it never delivered on the earnings. And, as time wore on, the large international carriers became the owners. Between them, the five big owners account for about 90 per cent of the company.

Not that a profit was paramount for them. Virgin Australia was as much a strategic ploy as it was a financial investment.

For Singapore, Etihad, Branson, the two Chinese carriers and, at one stage, Air New Zealand, Virgin Australia offered a full service and cut price domestic network that lifted the viability of their international businesses.

They could send international tourists to almost anywhere in the country at an affordable price.

Since Paul Scurrah took over the running of Virgin a year ago, there’s been a tighter focus on the bottom line.

He’s scaled down many of Borghetti’s more grandiose visions, chopped routes and delayed aircraft purchases in an effort to reduce costs and lift margins.

But it wasn’t quite enough to counter the crisis that has crippled the industry. If Virgin survives voluntary administration, it will be in a far more modest form.

One-and-a-half airlines.

Cre: abc.net

Nguyen Xuan Nghia – COMM